The production pipe-line of an interactive VR experience

Many of you will probably already know about the production pipe-line of a VR experience – or a video game – but we still believe it is important to clarify the...

Many of you will probably already know about the production pipe-line of a VR experience – or a video game – but we still believe it is important to clarify the...

The focus of our VR experience is definitely the human relationship. Time, in ‘Vajont’, passes in the presence of characters who, for the whole duration of the piece,...

To date, about a year and a half has passed since Artheria was founded. I have always found it a little difficult to explain to people outside what we do, which sometimes seems a...

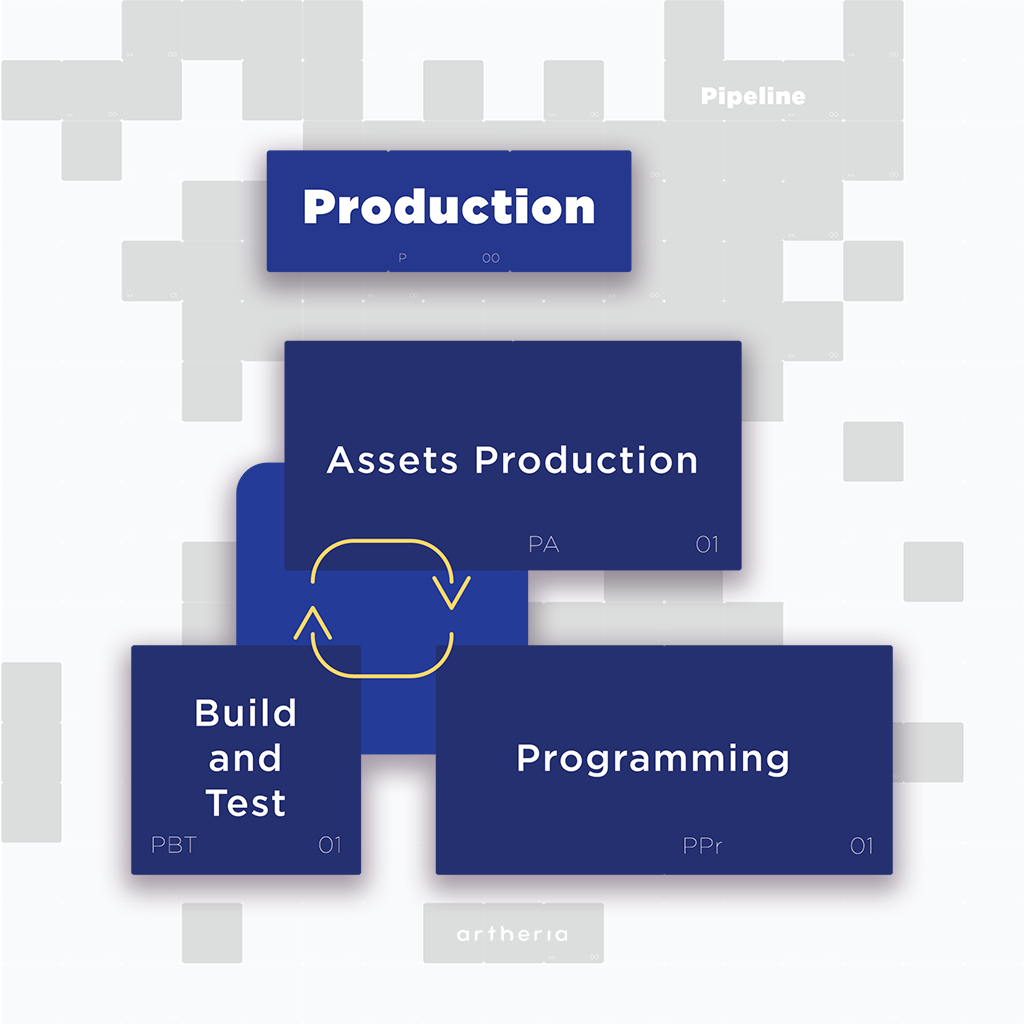

Many of you will probably already know about the production pipe-line of a VR experience – or a video game – but we still believe it is important to clarify the process we have followed.

Before going into more detail, we would like to spend a few words to describe a process certainly better known and undoubtedly more linear, but capable of tracing the beginning of the path – in addition to many other languages - VR has also followed. We are talking about a not-too-distant ancestor: the world of cinema.

The production process in the world of cinema is essentially divided into three phases: pre-production, production, and post-production.

Obviously, we do not claim to be exhaustive with these few words; for specific insights on the cinematic pipe-line, we invite you to do a dedicated web search, from which you will surely find many dedicated articles.

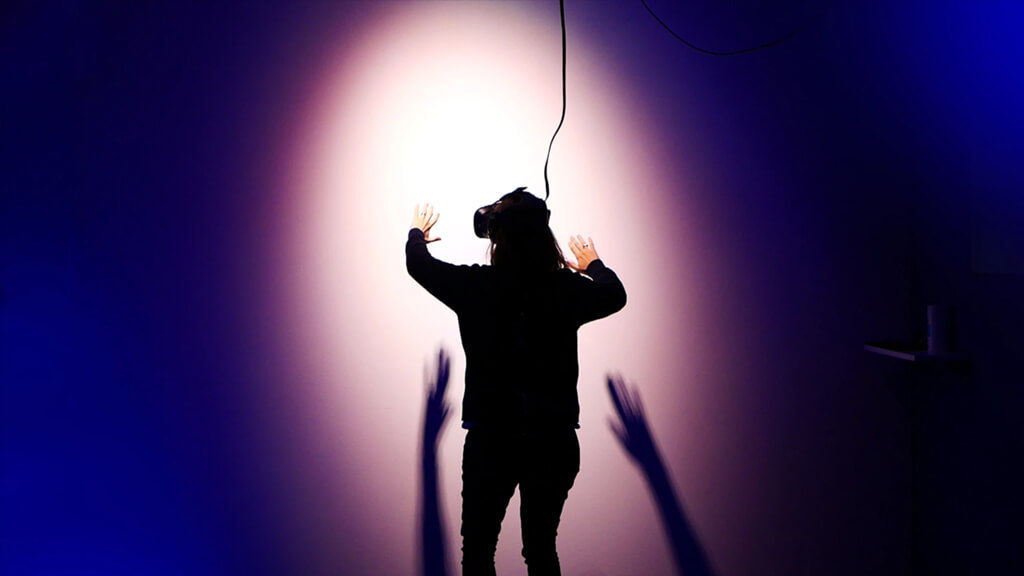

Well, after this first, rightful premise, let’s come back to us: how is the cinematic pipe-line different from the pipe-line of a Virtual Reality experience?

Actually, it is enough to reflect on the concept of real time to find an answer: our pipe-line doesn’t foresee a real post-production phase, simply because – at the moment you go into production – the various phases branch out and take place at the same time.

Therefore, we will only have two major stages: pre-production and production (or development).

N.B. The following article is a schematization of the main phasis and figures involved in the realization of a CGI interactive VR experience (i.e., a video game). More information can be found in the links added to this post, but we would like to remind you that the aim of this article is exclusively to provide a global vision, without going into the specifics of each sector or category.

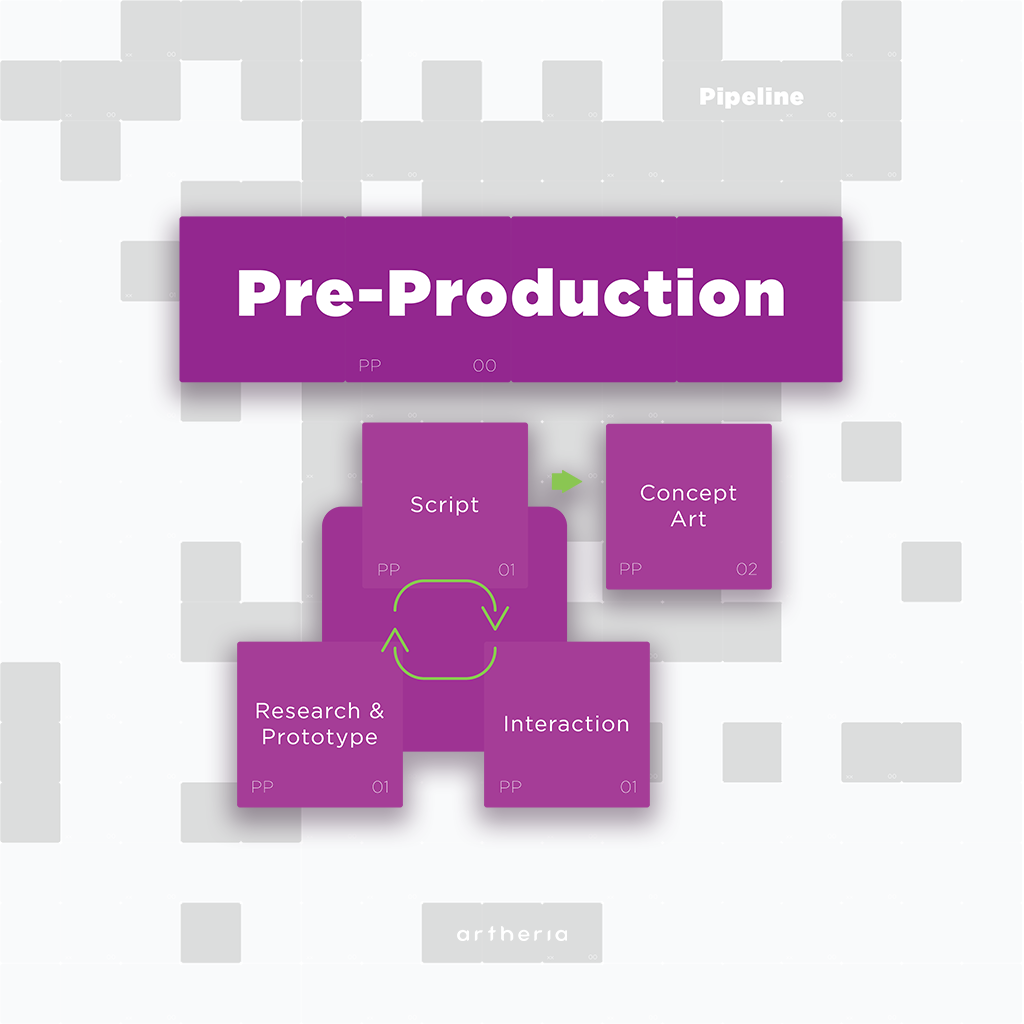

This is when all the guidelines for the future development of the project are dictated. We can assert that this is the moment when we ask ourselves: what makes the project we aim to realize interesting, attractive, and valuable?

Unlike cinema – where an interesting way of telling a good story is often the fundamental factor in the success of a film – in the world of VR experiences this is not always true. People are not called upon to look passively at what is happening around them, but to take an active part in it.

It follows that the screenplay of an interactive VR experience goes hand in hand with the study of the interactions the participant is called upon to make. The concept of gameplay is something very broad, which sums up the quality of the complete gaming experience: not only a compelling storyline, but also interactions integrated coherently with the narrative, with modes of execution (a sequence of movements or keys to press) that are easy to remember and, in a certain sense, instinctive. None of us would try to close a window by touching our toes, right?

Screenplays and interactions therefore are strongly connected, influencing each other side by side, with research. Each idea, in fact, must not work well only on paper. It is necessary to understand from the very beginning what will be the most effective way to achieve the objective, what the potential is, and what the limits are of that particular technology, including costs.

A general prototype of the experience will then be made, in order to understand the feasibility of the identified road, the functionality of the interactions and the general level of fun achieved, in order to make improvements and fix initial bugs.

These three steps (writing the screenplay, defining the interactions, doing research) influence each other continuously. What you get at the end of these steps is halfway between a movie script and a Game Design Document (GDD).

Having thoroughly defined the structure of the experience, pre-production is completed by working on the visual aspects of the project.

The concept artist does an in-depth study of the characters and the environment, and works on the overall layout of the experience. The artist’s story boards will serve as guidelines for the modelers, the texture artists, and the lighting artists.

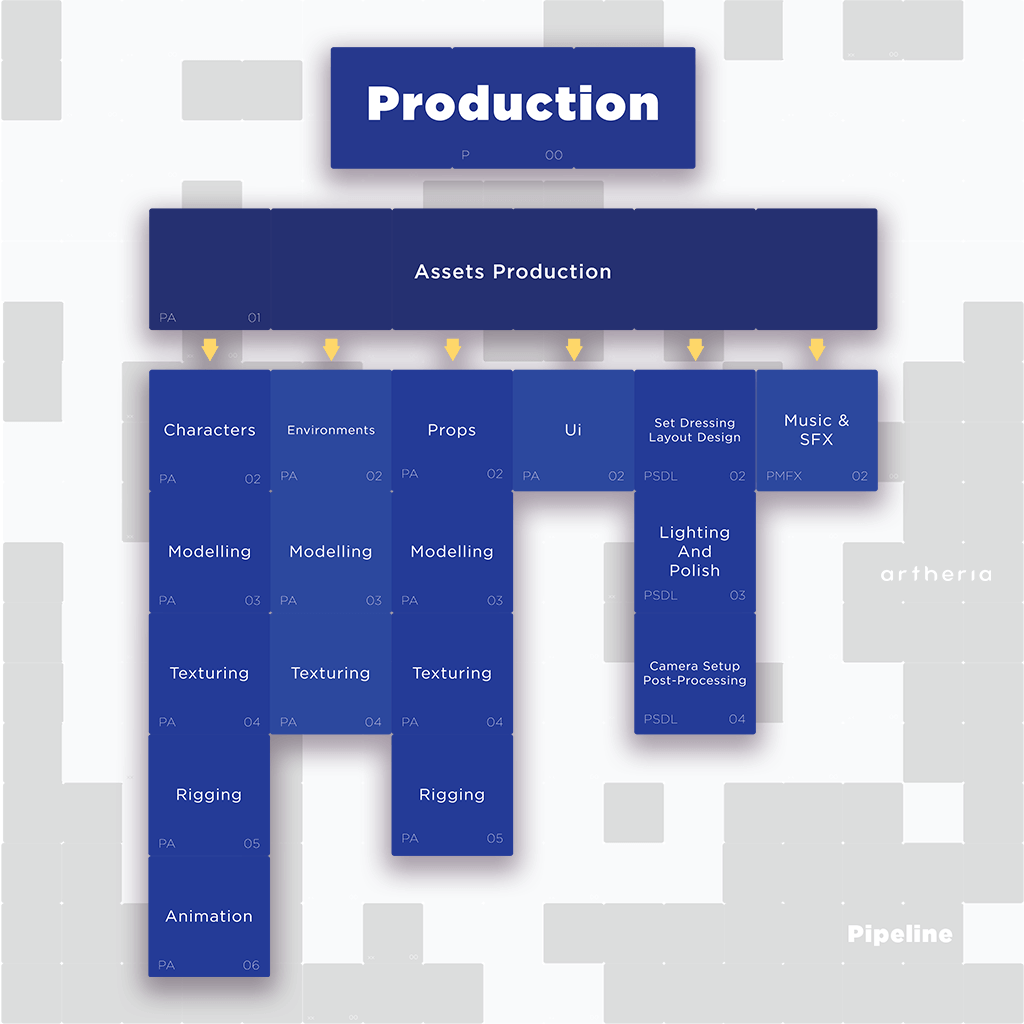

Having identified the main structure of the experience and its characteristic elements, we come to the actual production phase. The various artists provide for the realization of the game elements: the characters, environment, props, User-Interface, sound-effects, and soundtrack.

The production pipeline of the 3D elements (characters, environment and objects) varies slightly, depending on what the expected behavior of each element will be. Just as it is expected that the organic figures will move, walk, run and talk, it is necessary, for example, to make sure that windows are able to rotate on their hinges to open, etc.

Anyway, their realization has a common beginning.

On the left of the picture: organic modeling of a character. On the right: hard-surface modeling of a prop.

Characters, environment and props are then modeled in 3D, using dedicated software. The professionals involved in their creation are called character artists and environment artists.

You can deepen this phase by discovering how we modeled:

On the left of the picture: texturing of a character. On the right: prop texturized.

The 3D assets are then texturized. Texturing and modeling are interesting and creative processes. A good texture artist not only gives the elements the right color, but also works on the level of narration and truthfulness. What can we deduce from some paint stains on a character’s shirt – what life does he lead, how does he spend his days?

You can deepen this phase by discovering how we texturized:

Unlike the environment, the characters and props are therefore subjected to rigging: the construction of a sort of virtual ‘skeleton’ and structure that allows assets to move realistically.

If this operation is usually intuitive for environmental props (for example, it is quite easy to define the hinge as the rotation axis of a window), this is not equally true for organic characters. Not only is the amount of movements they need to be able to make much more extended, but also the way their body deforms affects the perception of realism. Elbow, armpit, and groin bends are fundamental factors for the level of general truthfulness, not to mention facial mimicry.

At the end of the rig, the organic characters (and the props that needs to) are animated. N.B. The texturing and rigging phases are not necessarily to be considered sequential: they can also be considered simultaneous.

You can deepen this phase reading the post “Character rigging for virtual reality “

To finalize the production of the assets – this is the technical name of all the various elements – paralleling the sound effects, the soundtrack, and the GUI (if any) are produced.

In this devBlog you can learn about the importance of audio in Virtual Reality and discover some examples of GUI (Graphic User Interface).

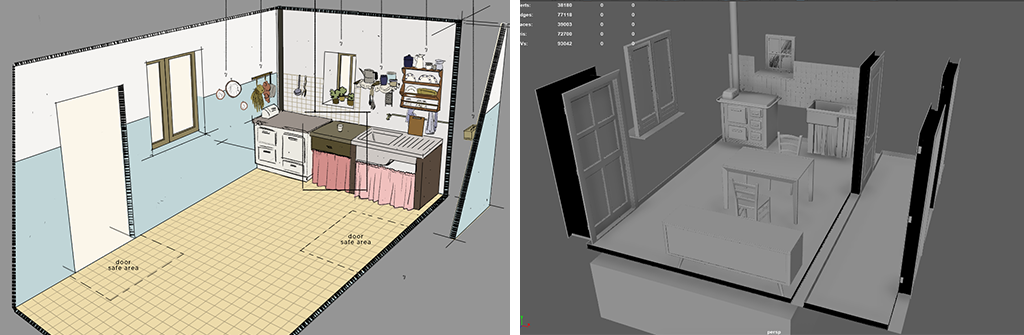

On the left of the picture: the concept of the environment. On the right: the placing of the props inside the environment, following the concept.

The props are integrated within the environment, setting up a real virtual set. This operation takes the name of set dressing and follows what was defined in the layout design phase.

The layout design of each VR experience (or video game) takes into account the main objectives and movements that the participant is called to perform within the experience itself, assembling the environmental elements and interacting in a functional way. We cannot think of hiding the treasure map above the closet without placing a ladder nearby.

Since our experience is thought to be enjoyed in a physical place (the Venice Biennale), our studies also involved the design of a real scenography which had to integrate well with the virtual one. We, therefore, took into account not only the ‘virtual’ movements required, but also the real ones by studying a path and considering the management of the queue of people waiting. We will treat this subject in more detail in another post.

Lighting, as in cinema, is a fundamental component of the construction of the mood of a piece. Over the years, the new engines of real-time rendering have reached results likely to be credible, offering an increasingly wide creative range. This is also the time for scene optimization, i.e. to carry out a series of technical improvements that allow you to save memory and computing power and to ensure a consistent frame rate.

You can deepen this phase reading the post “Lighting for VR“

The next step is identifying the right settings of the virtual camera, almost entirely following the operations done in reality; that is, setting exposure, aperture, depth of field, etc. Post-processes are then applied for the color grading and fine-tuning of the image: curves, tone-mapping, vignetting and so on.

The programming department takes care of the whole coding part of the experience.

As part of coding, we identify the programming of the level, the interactions, and the artificial intelligence of the characters.

Finally, we proceed with the creation of the build – a sort of ‘playable’ export of the project – and the tests.

Are we done? Unfortunately, not.

Unlike cinema, where we can define the production process as linear, – a film hardly goes back to the editing phase, after being color-corrected, unless it’s to add some scenes based on the director’s request – the pipeline processing of a VR experience is much more chaotic. Testing may highlight usability or programming issues, the lighting may not work, texturing may not be as photo-realistic as it seemed on the PC monitor.

An experience can be considered as actually complete only when it is officially presented to the public – that is, when it is distributed.

But even then, there will always be an option to intervene in the release of subsequent upgrades.